Curbing the Office Jerk

Published on November 27, 2017

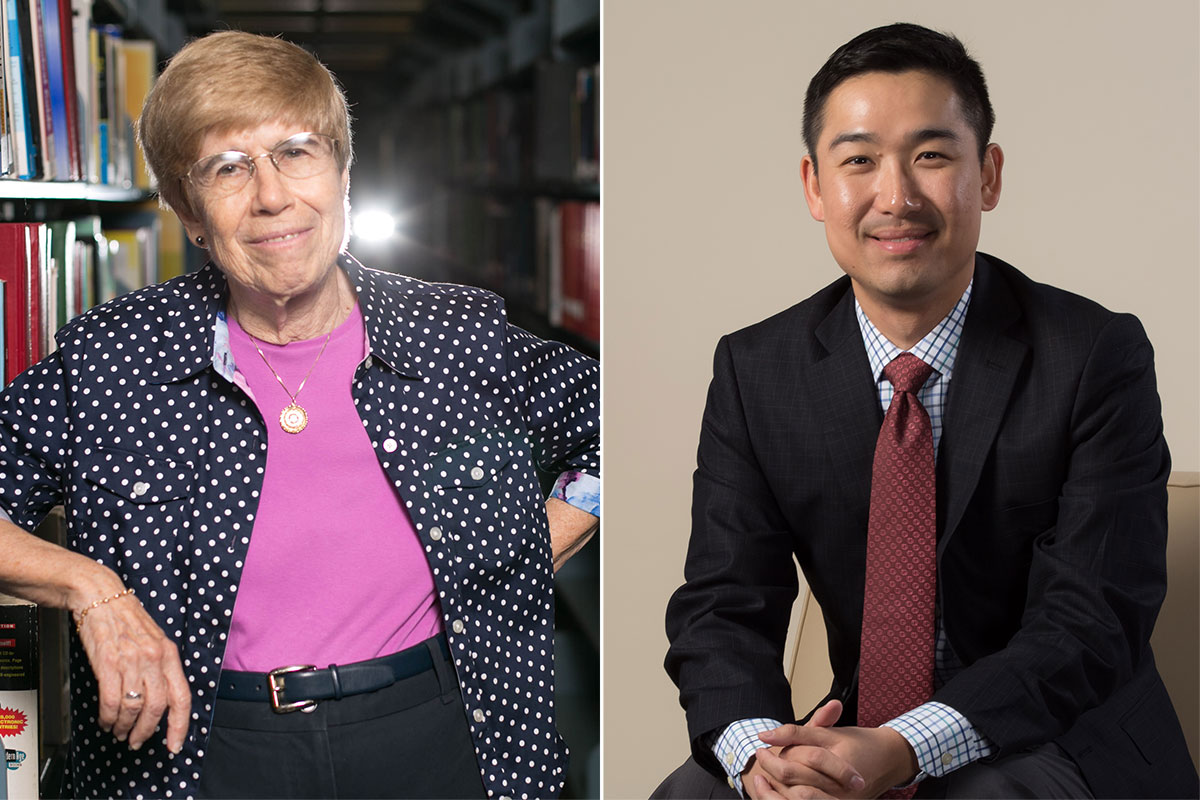

Larry J. Sachnowitz Professor of Marketing Betsy Gelb and Assistant Professor of Management Dejun “Tony” Kong stress the need to start a conversation about a shift of the mindset and a reinvention of work culture.

In business, one measurement isn’t reflected in official audits, yet has the potential to influence productivity, morale and overall success.

And the truth is, most of us keep score.

That unspoken count?

The number of “jerks” in your workplace.

According to research, most people (98 percent) exhibit “jerk-like” behavior at one time or another when they are at work. To make matters worse, a new study suggests that behaving badly may be correlated with getting more promotions.

Two Bauer College faculty members explore the phenomenon in an upcoming paper called “Curbing, Not Rewarding, Jerk Behavior on the Job.” In it, Assistant Professor of Management Dejun “Tony” Kong and Larry J. Sachnowitz Professor of Marketing Betsy Gelb stress the need to start a conversation about a shift of the mindset and a reinvention of work culture.

Being a jerk isn’t a good strategy for long-term success, they say, and addressing the problem will require an organizational mindset change that encourages collaboration rather than competition.

“I think we can change it, but it might not be a fast change,” Kong said. “There’s a dilemma…Many jerks actually deliver results.”

The researchers defined jerk behavior as engaging in uncivil behavior such as yelling, putting down a colleague, interrupting or shifting blame in a way that benefits them. In a survey of more than 700 alumni of a well-known business school, more than 40 percent admitted to not listening, or putting down a co-worker’s suggestion by interrupting with “no,” “but” or “however,” at some point during the previous three years.

For years, Kong and Gelb had heard MBA students express frustration that peers or superiors with bad behavior seemed to get ahead more than those perceived as nice. But Kong and Gelb wanted to see if those anecdotes could be backed up by research evidence.

Controlling for a host of other demographic and job-related factors, Kong and Gelb were somewhat surprised to find a positive correlation, but warn such gains are short-lived.

“In the long run, it’s about what is sustainable,” Kong said. “Morale is going to be decreased, the culture is going to be more toxic, productivity in the long run is going to be less. It may be very enticing to get results in the short run. But promoting jerks will ruin you in the long term. “

The authors hope to raise awareness of the issue, and to encourage a shift of thinking in the workplace.

“You might restructure things so that there are team performance reviews rather than individual incentives, so people are not competing against each other,” Kong said. “Redesign jobs to be more relational, encouraging interpersonal contact and collaboration, rather than just focused on task completion.”